The God Who Is There in The Francis A. Schaeffer Trilogy: Three Essential Books in One Volume by Francis A. Schaeffer. Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 1990, 199 out of 361 pages, $16.95

The God Who Is There in The Francis A. Schaeffer Trilogy: Three Essential Books in One Volume by Francis A. Schaeffer. Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 1990, 199 out of 361 pages, $16.95

The God Who Is There by Francis Schaeffer is a seminal work in twentieth century apologetics. Inspiring generations to follow, Schaeffer, an American philosopher, theologian and Presbyterian pastor, is one of the most recognized and respected Christian authors of all time. As his first book, The God Who Is There is one among an essential reading list including Escape From Reason, True Spirituality, How Should We Then Live and A Christian Manifesto. The four volume set, The Complete Works of Francis Schaeffer, is part of this reviewer’s Logos Bible software library. This presentation will give a broad overview and summary of the book, and offer several key points of analysis. The first point of analysis will be the line of despair, which naturally leads to discussion of propositional truth because it is the delineating factor. The steady progression of relativism and irrationality through various disciplines will be discussed with particular attention to theology and the implications to ecumenism. Schaeffer’s tactic of “taking the roof off” will be examined on the basis of the unbeliever’s inevitable leap into irrationality. Finally, the importance of compassion and consistency is emphasized. The review will attempt to show that the book is valuable for its prescient analysis of modern culture and powerful apologetic approach.

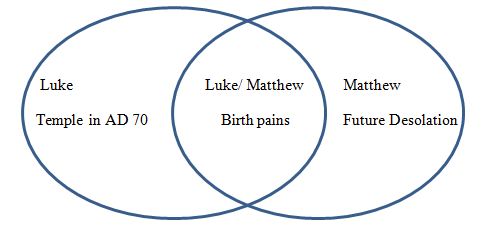

Schaeffer’s genius was his capacity to communicate difficult philosophical and theological issues to the average Christian. He begins by exposing the problem as a widening gulf growing between the older and the younger generations concerning the knowledge of truth or epistemology. In so doing, he rightly bemoans the mounting acceptance of relativism over antithesis. Of course, the book was first published in 1968 so that younger generation is now mature and relativism is deeply embedded in the public psyche. His analysis was prescient, because today there is an institutionalized divide where scientific truths are held as absolute but morals, values and religion are all relative and preference based. The book is divided into six sections of several chapters. In the first section dealing with the intellectual climate of the late twentieth century, Schaeffer demarcates a major shift in thought by “a line of despair” around 1935 (for the U.S.) which descends step wise through the disciplines of philosophy, the arts, general culture and finally theology.

In philosophy, Schaeffer was largely lamenting the then popular existentialist movement with its relativizing of truth. Even so, his critique applies equally to twenty-first century postmodernism. He draws the line of despair at Hegel with his dialectical synthesis but also traces the problem back to Aquinas with his division of “nature and grace” and an incomplete view of the biblical fall which held that man had an autonomous intellect.[1] He moves from Hegel to Kierkegaard who was the first under the line by asserting that a leap of blind faith was necessary to becoming a Christian. With this leap into non-reason, Schaeffer posits him as the father of modern existential thought.

The epistemological jump into subjective non-reason is the cause for the despair and the crux of Schaeffer’s critique. It undermines hope. Schaeffer observed, “As a result of this, from that time on, if rationalistic man wants to deal with the really important things of human life (such as purpose, significance, the validity of love), he must discard rational thought about them and make a gigantic, nonrational leap of faith.:”[2] This fuzzy way of thinking leaves no certainty in ultimate matters. While this leap is admitted by existentialists, other philosophies like logical positivism (or scientism) misleadingly lay claim to rationality. Even so, Schaeffer demonstrates positivism’s incoherence in that it simply assumes the reliability of sense data without justifying it. Because it floats epistemologically in mid-air with no foundation, it is self-refuting. In this way, Schaeffer argues that blind faith in science and human progress is ultimately an irrational leap of faith as well. The genius of this book was in showing how this secular impetus in philosophy spread to the culture at large.

With no grounding or basis for truth in ultimate matters, art and music also began to reflect the secular despair. The visual arts lost all sense of realism and progressed from the hazy wash of the impressionists to the tortured figures in Picasso’s work. Schaeffer critiques and explains his impressions of figures like Mondrian, Duchamp and the Dada group in terms of man’s leap into non-reason. As art grew more abstract and impersonal so music lost its tonal center. John Cage is an example of a composer who sought to introduce randomness into his music. The absurdity of a composition of total silence is milestone along the descent.

One weakness in Schaeffer’s discussion is the neglect of viable Christian alternatives. When one compares the beauty and order of a J.S. Bach piece to a modern like Cage the line of despair stands out in sharp relief. Surely some Christian contemporaries of Schaeffer were producing viable art? But this seems to beg the question of Christians equitably competing in the contemporary artistic culture. There is surely an element of secular snobbery involved in the academy. Even those not inclined toward the sophisticated art forms are influenced in popular films and television. He makes a convincing case that the culture as a whole had fallen below the line.

What all disciplines share is the divided field of knowledge and the belief that truth is unknowable in ultimate matters. The trend toward despair is traced through the literature of Henry Miller and Dylan Thomas and the point is well illustrated. He observes that things like purpose, morals and love are relegated to the domain of opinion. Even so, an exemplary aspect of Schaeffer’s critique is that it is compassionate. After dissecting the absurdity seen in modern art forms he reminds the reader, “There is nothing more ugly than a Christian orthodoxy without understanding or without compassion.”[3] Man’s despair is real and it is epistemic of relativism and a deep lack of real hope. He frames the state of affairs as an opportunity for the church to compassionately declare that God is really there.

The second section deals with the new theology and the departure from biblical Christianity. He argues that theology is simply the last to fall along the same lines as philosophy and the arts. Theologians adopted purely rationalistic approaches and the demythologization program which ensured not only excised the supernatural but Christ as well. Of course, foundational to New Testament theology is the fall of man and the effects of Darwinian thought are still echoing today. Schaeffer observed, “Take away the first three chapters of Genesis, and you cannot maintain a true Christian position nor give Christianity’s answers.” This issue of man’s sinfulness and justification is crucial to coherent theological dialog. A major strength of this book is its scathing critique of liberal theology

Whereas Lesslie Newbigin advocates a generous ecumenism in an organization like the World Council of Churches, Schaeffer seems more realistic as to the state of affairs. The pivot point is the depravity of man and justification before a Holy God. He writes that justification means to be acquitted from actual guilt, “an absolute personal antithesis.”[4] This is often the point of tension with liberal theology which has important implications or ecumenism:

We may not play with the new theology even if we may think we can turn it to our advantage. This means, for example, we must beware of cooperation in evangelistic enterprises which force us into a position of accepting the new theology as Christian. If we do this, we have cut the ground from under the biblical concept of the personal antithesis of justification.[5]

Schaeffer critiques Barthian neo-orthodoxy as well as liberal Catholic thought, labeling it as ostensibly “semantic mysticism.” This did not happen overnight and he traces it back to Aquinas’ division of nature and grace, which sought to find a corporate meaning, to more desperate modern formula of the irrational over the rational, with no hope of unity. He argues that because the new theology has divorced faith from reason you can testify to it but you cannot really discuss it. Indeed, finding the point of irrationality and pressing it to the forefront of discussion is at the heart of Schaeffer’s apologetic.

Foundational to Schaeffer’s thought is that God has communicated real propositional truth to man in the Bible. It follows necessarily that the antithesis of God’s truth is false and this is the basis of what he calls “taking the roof off.” The idea is that secular presuppositions invariably contain an incoherence that when pressed lead to an absurd and intolerable conclusion. Without this realization, the unbeliever lives comfortably under a roof of irrational beliefs which shield him from the outside world. When the roof is removed, reality comes crashing in. The task of the apologist is to find a point of tension and lovingly yet firmly carry it through so the incoherence is obvious. If one can lead the unbeliever to see that his own system is unlivable, then there is a real opportunity to provide biblical answers. Taking the roof off is often painful because the real dilemma of modern man is moral and he is culpable to God. This is the truth of the Gospel which is often most offensive. There really are no “good” people.

The supernatural atoning work which Christ finished on the cross is the content of real biblical faith. But because they may never read a Bible, Schaeffer argues that the final apologetic is how the world sees Christians living individually and corporately. It follows that the message of the final section of the book is one of housecleaning. Individually, as an ambassador of Christ to the fallen world one must examine his own presuppositions with equal rigor. In an increasingly biblically illiterate (or skeptical) culture, Christianity is judged by the words and actions of Christians. Corporately, when Christians do not live as if God is really there, then it is hard to expect the world to believe our message.

The book teaches that a cold hearted orthodoxy is a poor substitute for loving authenticity. While a very strong case is made for the latter, a weakness in a book with this title (and perhaps indicative of Schaeffer’s training under Conelius Van Til) is that there is a conspicuous lack of evidential arguments for the existence of God. Nevertheless, because God is really there and calls the world to worship Him, Schaeffer’s apologetic works. The pride of life is a constant barrier and Schaeffer asserts, “Men turn away in order not to bow before the God who is there. This is the ‘scandal of the cross.’”[6] The challenge to believers is to live in way that shows His presence.

This brief summary and analysis of The God Who Is There sought to illustrate the value of the book for its scrutiny of Western culture, concept of truth and apologetic method. The so-called “new theology” was discussed as concession to the relativistic philosophy. It was agreed that man is truly fallen and guilty in the eyes of the Holy God who is really there. Because of this, the task of modern evangelism and apologetics is often to expose the incoherence of secular presuppositions in a firm yet compassionate way. Relativism is ingrained in the secular culture but there is also plenty of work to be done within the evangelical community. In the end, it seems that these points support the idea that this book is still extremely valuable for study.

[1]Francis A. Schaeffer, The God Who Is There in The Francis A. Schaeffer Trilogy: the Three Essential Books in One Volume. (Westchester, Ill.: Crossway Books, 1990), 211.

[2] Schaeffer, The God, 16.

[3] Schaeffer, The God, 34.

[4] Schaeffer, The God, 112.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Schaeffer, The God, 111.