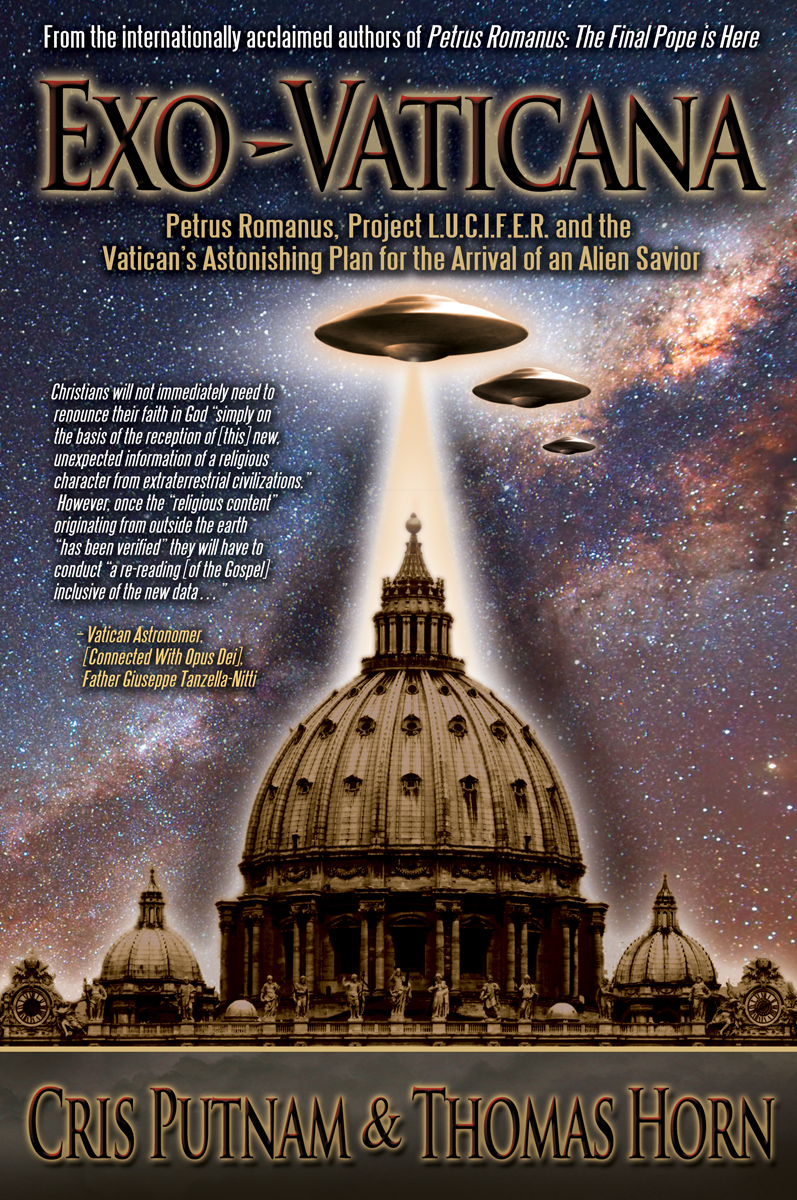

In our book, Petrus Romanus, published last Spring we commented on the Vatican’s ambition to get a foothold in Jerusalem. We wrote about an obscure under the table deal concerning the Hall of the Last Supper on Mount Zion, only one journalist that I am aware of, Giulio Meotti, was even mentioning it:

In our book, Petrus Romanus, published last Spring we commented on the Vatican’s ambition to get a foothold in Jerusalem. We wrote about an obscure under the table deal concerning the Hall of the Last Supper on Mount Zion, only one journalist that I am aware of, Giulio Meotti, was even mentioning it:

While the papal power play is likely to progress by the time this book returns from the printer, on February 4, 2012, an op-ed piece ran on the Israeli news site Ynet News titled, “Don’t Bow to the Vatican.” The editorial by Italian journalist Giulio Meotti opposes the Vatican’s designs on Jerusalem, and speaks in the past tense referencing the sovereignty over the Cenacle (which houses the Hall of the Last Supper and King David’s tomb):

Don’t Bow to the Vatican

Israel reached an historical agreement with the Vatican to give up some sort of sovereignty over the “Hall of the Last Supper” on Mount Zion in Jerusalem. The Vatican will now have a foothold at the site: Israel agreed to give the Vatican first priority in leasing opportunities and access to it. SourceAs this book goes off to the printer we have not been able to verify the past-tense phrasing “Israel reached an historical agreement with the Vatican” with a concrete piece of documentation, but it appears that the Vatican has reached its long-sought goal of sovereignty over at least one site on Mount Zion. (Petrus Romanus p. 385-386)

If our thesis that the next pope is the biblical false prophet is correct, then establishing a foothold in Jerusalem is an essential piece of the puzzle. Almost a year had passed with media silence on the issue… that is until today, now we can consider it accomplished:

Israel reaches historic agreement with Vatican, seating them at Last Supper site

The Pope will finally have official seat in the Last Supper room on Mount Zion, Jerusalem

Outgoing Deputy Foreign Minister Danny Ayalon: This is a historic achievement and a symbol that will encourage Christian tourism.

By Shlomo CesanaSource: here

Of course we had a lot more to say about the Vatican’s Jerusalem ambitions and given this turn of events you might want to refresh your memory. If you would like a signed copy form me personally along with the data DVD library follow the link here or under “My Books” above.