by Cris Putnam

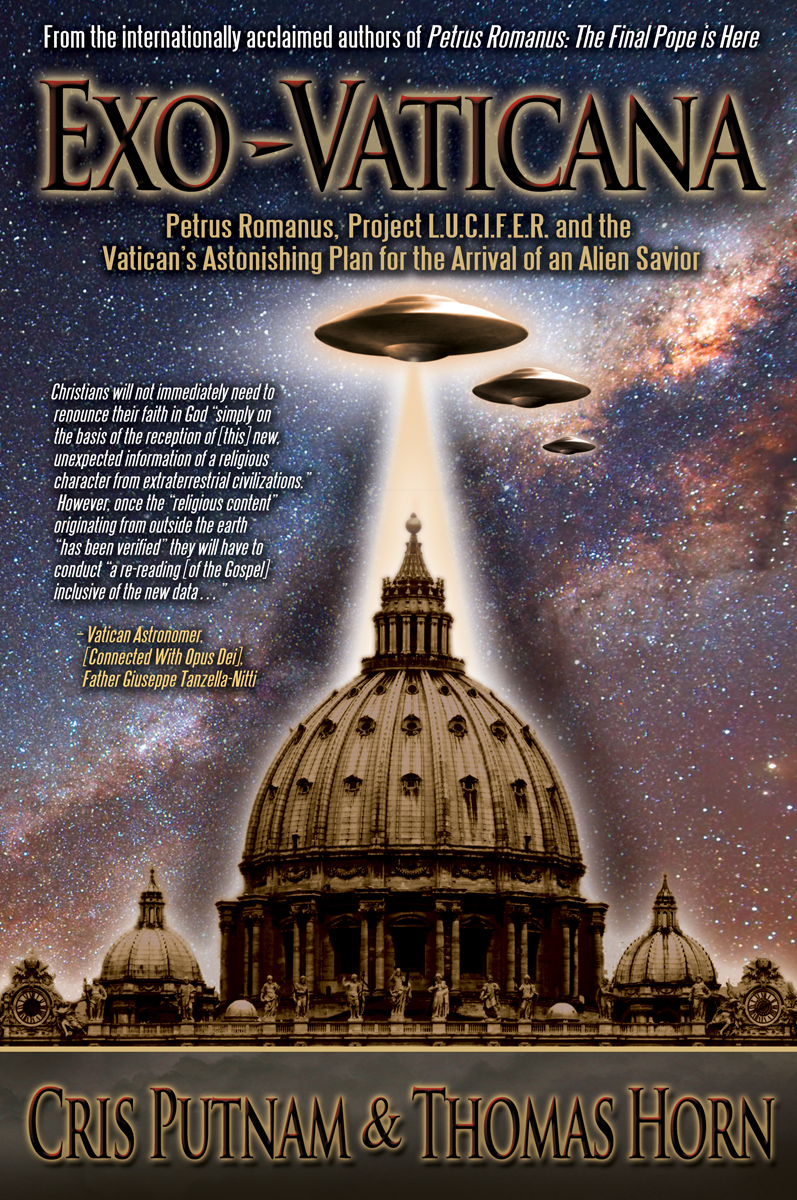

Ever since George Lucas’ Star Wars, there has been an increasing tendency in evangelicalism to think of the Holy Spirit akin to “the Force.” In the culture at large, it is even worse. According to recent Pew Forum statistics 25% of Americans who believe in God, think of God as an impersonal force.[1] Amongst Christians, doctrine of the trinity leads to similar confusion. The classical understanding is one God in three persons. However, many evangelicals tend to view the Holy Spirit as a force employed by God the Father. In his seminal Christian Theology, Millard Erickson noted, “We are not dealing here with an impersonal force. This point is especially important at a time in which pantheistic tendencies are entering Western culture through the influence of Eastern religions.”[2] I documented the influx of pantheistic thought through the work of Jesuit Pierre Teilhard de Chardin in Exo-Vaticana. In a recent Facebook discussion, doubt was expressed concerning the personhood of the Holy Spirit based on the following argument:

Ever since George Lucas’ Star Wars, there has been an increasing tendency in evangelicalism to think of the Holy Spirit akin to “the Force.” In the culture at large, it is even worse. According to recent Pew Forum statistics 25% of Americans who believe in God, think of God as an impersonal force.[1] Amongst Christians, doctrine of the trinity leads to similar confusion. The classical understanding is one God in three persons. However, many evangelicals tend to view the Holy Spirit as a force employed by God the Father. In his seminal Christian Theology, Millard Erickson noted, “We are not dealing here with an impersonal force. This point is especially important at a time in which pantheistic tendencies are entering Western culture through the influence of Eastern religions.”[2] I documented the influx of pantheistic thought through the work of Jesuit Pierre Teilhard de Chardin in Exo-Vaticana. In a recent Facebook discussion, doubt was expressed concerning the personhood of the Holy Spirit based on the following argument:

Many will point to Scriptures like John 14:26 as proof that the Holy Spirit is a person:

But the Comforter, which is the Holy Ghost, whom the Father will send in my name, he shall teach you all things, and bring all things to your remembrance, whatsoever I have said unto you. (John 14:26 KJV)

The problem is, the Greek word used here for “he” is ekeinos (Strong’s 1565), which is a demonstrative pronoun that means “that, that one there, yonder” as opposed to the standard pronoun autos (Strong’s # 846), which is a personal pronoun meaning, “he, she, it, they, them, same” as seen repeatedly for instance in 1 John 3:24:

And he that keepeth his commandments dwelleth in him, and he in him. And hereby we know that he abideth in us, by the Spirit which he hath given us. (1 John 3:24 KJV)

This is a poor argument. What is defined as “the problem” above is John’s use of ἐκεῖνος which means “that” or “that one.” The force of the argument is that if John wanted us to understand a male person he would have simply used αὐτός which translates “he, she, it” depending on grammatical gender. It implies his choice of the demonstrative imparts ambiguity upon the personhood of the Holy Spirit, but this is simply not so and reflects a lack of understanding basic Greek grammar.

Greek employs a lot more pronoun forms than English: personal, reflexive, demonstrative, indefinite, interrogative, relative and reciprocal. Demonstratives are used when the author wants to communicate where something is in relation to the speaker/writer and there are two forms near and far. In this case, it was a distance in time.

demonstrative pronoun. n. A pronoun that serves as a pointer or indicates where something is in relation to the speaker/writer (Lat. demonstrare, “to point out”). Near demonstratives (this and these) speak of things that are relatively close; far demonstratives (that and those), of things that are relatively distant. The latter are sometimes distinguished as demonstrative adjectives.[3]

John chose to use a demonstrative pronoun in John 14:26 because the Holy Spirit was not yet present, but in Greek there is no ambiguity concerning gender because he chose the masculine form. What is important is that John could have chosen the neuter form (and technically should have) but he didn’t for a reason. After the arrival of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, it makes sense that 3rd person singular would be used rather than a demonstrative pronoun. Attested in 1 Corinthians 12:11, which states that the recipients of the various spiritual gifts are “the work of one and the same Spirit, and he gives them to each one, just as he determines.” (βούλομαι, verb, present, middle/passive, indicative, third person, singular) When Jesus spoke the Holy Spirit had not yet come, when Paul wrote 1 Corinthians he had. This demonstrates that simply using a concordance to translate Greek words to English is not sufficient for biblical exegesis.

What makes this particularly dangerous is that these types of misunderstandings have a long checkered history of spawning cults. In apologetic theology a cult is defined:

A cult of Christianity is a group of people, which claiming to be Christian, embraces a particular doctrinal system taught by an individual leader, group of leaders, or organization, which (system) denies (either explicitly or implicitly) one or more of the central doctrines of the Christian faith as taught in the sixty-six books of the Bible.[4]

The personhood of the Holy Spirit is a central doctrine of classical Christianity. Denying it qualifies as a cultic belief akin to other groups like the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Theology is important. Matt Slick has a nice outline detailing the biblical basis for the classic doctrine of the Spirit here.

[1] http://www.pewforum.org/2008/06/01/u-s-religious-landscape-survey-religious-beliefs-and-practices/

[2] Millard J. Erickson, Christian Theology., 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1998), 875–876.

[3] Matthew S. DeMoss, Pocket Dictionary for the Study of New Testament Greek (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2001), 44.

[4] Alan Gomes, Unmasking the Cults (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1995), 7.