Here is session two form my workshop at the future congress last summer.

Book Review The God Who is There by Francis Schaeffer

The God Who Is There in The Francis A. Schaeffer Trilogy: Three Essential Books in One Volume by Francis A. Schaeffer. Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 1990, 199 out of 361 pages, $16.95

The God Who Is There in The Francis A. Schaeffer Trilogy: Three Essential Books in One Volume by Francis A. Schaeffer. Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 1990, 199 out of 361 pages, $16.95

The God Who Is There by Francis Schaeffer is a seminal work in twentieth century apologetics. Inspiring generations to follow, Schaeffer, an American philosopher, theologian and Presbyterian pastor, is one of the most recognized and respected Christian authors of all time. As his first book, The God Who Is There is one among an essential reading list including Escape From Reason, True Spirituality, How Should We Then Live and A Christian Manifesto. The four volume set, The Complete Works of Francis Schaeffer, is part of this reviewer’s Logos Bible software library. This presentation will give a broad overview and summary of the book, and offer several key points of analysis. The first point of analysis will be the line of despair, which naturally leads to discussion of propositional truth because it is the delineating factor. The steady progression of relativism and irrationality through various disciplines will be discussed with particular attention to theology and the implications to ecumenism. Schaeffer’s tactic of “taking the roof off” will be examined on the basis of the unbeliever’s inevitable leap into irrationality. Finally, the importance of compassion and consistency is emphasized. The review will attempt to show that the book is valuable for its prescient analysis of modern culture and powerful apologetic approach.

Schaeffer’s genius was his capacity to communicate difficult philosophical and theological issues to the average Christian. He begins by exposing the problem as a widening gulf growing between the older and the younger generations concerning the knowledge of truth or epistemology. In so doing, he rightly bemoans the mounting acceptance of relativism over antithesis. Of course, the book was first published in 1968 so that younger generation is now mature and relativism is deeply embedded in the public psyche. His analysis was prescient, because today there is an institutionalized divide where scientific truths are held as absolute but morals, values and religion are all relative and preference based. The book is divided into six sections of several chapters. In the first section dealing with the intellectual climate of the late twentieth century, Schaeffer demarcates a major shift in thought by “a line of despair” around 1935 (for the U.S.) which descends step wise through the disciplines of philosophy, the arts, general culture and finally theology.

In philosophy, Schaeffer was largely lamenting the then popular existentialist movement with its relativizing of truth. Even so, his critique applies equally to twenty-first century postmodernism. He draws the line of despair at Hegel with his dialectical synthesis but also traces the problem back to Aquinas with his division of “nature and grace” and an incomplete view of the biblical fall which held that man had an autonomous intellect.[1] He moves from Hegel to Kierkegaard who was the first under the line by asserting that a leap of blind faith was necessary to becoming a Christian. With this leap into non-reason, Schaeffer posits him as the father of modern existential thought.

The epistemological jump into subjective non-reason is the cause for the despair and the crux of Schaeffer’s critique. It undermines hope. Schaeffer observed, “As a result of this, from that time on, if rationalistic man wants to deal with the really important things of human life (such as purpose, significance, the validity of love), he must discard rational thought about them and make a gigantic, nonrational leap of faith.:”[2] This fuzzy way of thinking leaves no certainty in ultimate matters. While this leap is admitted by existentialists, other philosophies like logical positivism (or scientism) misleadingly lay claim to rationality. Even so, Schaeffer demonstrates positivism’s incoherence in that it simply assumes the reliability of sense data without justifying it. Because it floats epistemologically in mid-air with no foundation, it is self-refuting. In this way, Schaeffer argues that blind faith in science and human progress is ultimately an irrational leap of faith as well. The genius of this book was in showing how this secular impetus in philosophy spread to the culture at large.

With no grounding or basis for truth in ultimate matters, art and music also began to reflect the secular despair. The visual arts lost all sense of realism and progressed from the hazy wash of the impressionists to the tortured figures in Picasso’s work. Schaeffer critiques and explains his impressions of figures like Mondrian, Duchamp and the Dada group in terms of man’s leap into non-reason. As art grew more abstract and impersonal so music lost its tonal center. John Cage is an example of a composer who sought to introduce randomness into his music. The absurdity of a composition of total silence is milestone along the descent.

One weakness in Schaeffer’s discussion is the neglect of viable Christian alternatives. When one compares the beauty and order of a J.S. Bach piece to a modern like Cage the line of despair stands out in sharp relief. Surely some Christian contemporaries of Schaeffer were producing viable art? But this seems to beg the question of Christians equitably competing in the contemporary artistic culture. There is surely an element of secular snobbery involved in the academy. Even those not inclined toward the sophisticated art forms are influenced in popular films and television. He makes a convincing case that the culture as a whole had fallen below the line.

What all disciplines share is the divided field of knowledge and the belief that truth is unknowable in ultimate matters. The trend toward despair is traced through the literature of Henry Miller and Dylan Thomas and the point is well illustrated. He observes that things like purpose, morals and love are relegated to the domain of opinion. Even so, an exemplary aspect of Schaeffer’s critique is that it is compassionate. After dissecting the absurdity seen in modern art forms he reminds the reader, “There is nothing more ugly than a Christian orthodoxy without understanding or without compassion.”[3] Man’s despair is real and it is epistemic of relativism and a deep lack of real hope. He frames the state of affairs as an opportunity for the church to compassionately declare that God is really there.

The second section deals with the new theology and the departure from biblical Christianity. He argues that theology is simply the last to fall along the same lines as philosophy and the arts. Theologians adopted purely rationalistic approaches and the demythologization program which ensured not only excised the supernatural but Christ as well. Of course, foundational to New Testament theology is the fall of man and the effects of Darwinian thought are still echoing today. Schaeffer observed, “Take away the first three chapters of Genesis, and you cannot maintain a true Christian position nor give Christianity’s answers.” This issue of man’s sinfulness and justification is crucial to coherent theological dialog. A major strength of this book is its scathing critique of liberal theology

Whereas Lesslie Newbigin advocates a generous ecumenism in an organization like the World Council of Churches, Schaeffer seems more realistic as to the state of affairs. The pivot point is the depravity of man and justification before a Holy God. He writes that justification means to be acquitted from actual guilt, “an absolute personal antithesis.”[4] This is often the point of tension with liberal theology which has important implications or ecumenism:

We may not play with the new theology even if we may think we can turn it to our advantage. This means, for example, we must beware of cooperation in evangelistic enterprises which force us into a position of accepting the new theology as Christian. If we do this, we have cut the ground from under the biblical concept of the personal antithesis of justification.[5]

Schaeffer critiques Barthian neo-orthodoxy as well as liberal Catholic thought, labeling it as ostensibly “semantic mysticism.” This did not happen overnight and he traces it back to Aquinas’ division of nature and grace, which sought to find a corporate meaning, to more desperate modern formula of the irrational over the rational, with no hope of unity. He argues that because the new theology has divorced faith from reason you can testify to it but you cannot really discuss it. Indeed, finding the point of irrationality and pressing it to the forefront of discussion is at the heart of Schaeffer’s apologetic.

Foundational to Schaeffer’s thought is that God has communicated real propositional truth to man in the Bible. It follows necessarily that the antithesis of God’s truth is false and this is the basis of what he calls “taking the roof off.” The idea is that secular presuppositions invariably contain an incoherence that when pressed lead to an absurd and intolerable conclusion. Without this realization, the unbeliever lives comfortably under a roof of irrational beliefs which shield him from the outside world. When the roof is removed, reality comes crashing in. The task of the apologist is to find a point of tension and lovingly yet firmly carry it through so the incoherence is obvious. If one can lead the unbeliever to see that his own system is unlivable, then there is a real opportunity to provide biblical answers. Taking the roof off is often painful because the real dilemma of modern man is moral and he is culpable to God. This is the truth of the Gospel which is often most offensive. There really are no “good” people.

The supernatural atoning work which Christ finished on the cross is the content of real biblical faith. But because they may never read a Bible, Schaeffer argues that the final apologetic is how the world sees Christians living individually and corporately. It follows that the message of the final section of the book is one of housecleaning. Individually, as an ambassador of Christ to the fallen world one must examine his own presuppositions with equal rigor. In an increasingly biblically illiterate (or skeptical) culture, Christianity is judged by the words and actions of Christians. Corporately, when Christians do not live as if God is really there, then it is hard to expect the world to believe our message.

The book teaches that a cold hearted orthodoxy is a poor substitute for loving authenticity. While a very strong case is made for the latter, a weakness in a book with this title (and perhaps indicative of Schaeffer’s training under Conelius Van Til) is that there is a conspicuous lack of evidential arguments for the existence of God. Nevertheless, because God is really there and calls the world to worship Him, Schaeffer’s apologetic works. The pride of life is a constant barrier and Schaeffer asserts, “Men turn away in order not to bow before the God who is there. This is the ‘scandal of the cross.’”[6] The challenge to believers is to live in way that shows His presence.

This brief summary and analysis of The God Who Is There sought to illustrate the value of the book for its scrutiny of Western culture, concept of truth and apologetic method. The so-called “new theology” was discussed as concession to the relativistic philosophy. It was agreed that man is truly fallen and guilty in the eyes of the Holy God who is really there. Because of this, the task of modern evangelism and apologetics is often to expose the incoherence of secular presuppositions in a firm yet compassionate way. Relativism is ingrained in the secular culture but there is also plenty of work to be done within the evangelical community. In the end, it seems that these points support the idea that this book is still extremely valuable for study.

[1]Francis A. Schaeffer, The God Who Is There in The Francis A. Schaeffer Trilogy: the Three Essential Books in One Volume. (Westchester, Ill.: Crossway Books, 1990), 211.

[2] Schaeffer, The God, 16.

[3] Schaeffer, The God, 34.

[4] Schaeffer, The God, 112.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Schaeffer, The God, 111.

Book Review – Foolishness to the Greeks by Lesslie Newbigin

(This marks the first in a series of 4 book reviews concerning worldview apologetics)

Newbigin, Lesslie. Foolishness to the Greeks: the Gospel and Western Culture. Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1986,160 pages, Kindle Edition $9.92

Newbigin, Lesslie. Foolishness to the Greeks: the Gospel and Western Culture. Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1986,160 pages, Kindle Edition $9.92

This is a review and critique Lesslie Newbigin’s Foolishness to the Greeks: the Gospel and Western Culture. Newbigin was a Church of Scotland missionary serving in Tamil Nadu, India, who became a Christian theologian, bishop and author. He wrote many books including The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (1989) and The Open Secret: An Introduction to the Theology of Mission (1995). This book is primarily concerned with cross-cultural communication of the gospel with modem Western culture. As an experienced foreign missionary, he argues that missionaries must account for cultural baggage but the tendency in the West is to overlook it. He provides an apt critique to those who were, “confusing the gospel with the values of the American way of life without realizing what they were doing.” [1] Yet, particularly troubling to Newbigin back in 1986 and what is demonstrably more urgent today, is the decline of biblical Christianity in Western culture. He argues that a “pure Gospel” is largely an illusion because it is always presented linguistically and all language is culturally conditioned.[2] Indeed, the Gospel needs to be contextualized for one’s neighbors and Foolishness to Greeks is a cogent effort to that end. He concludes with seven suggestions and this paper will offer some brief analysis. This review will attempt to show that the book is extremely valuable for its analysis of Western culture but perhaps a little naïve in its ecumenical optimism.

He interacts with science, economics and politics and asks how the church can best affect culture. Discussion is offered on the ways the scientific revolution has changed people’s worldview. Accordingly, the author wrestles with the question of how the biblical text is viable for Westerners. He refers to Peter Berger’s plausibility structures, the social structure of ideas and practices that help one decide what to believe, as a means to show the Gospel has been compromised. Because reality is understood in cultural terms, he asks, “How can we move from the place where we explain the gospel in terms of our modern scientific world-view to the place where we explain our modern scientific world-view from the point of view of the gospel?”[3] This is important because the enlightenment not only brought new knowledge but also a new concept of human autonomy. People take a smorgasbord approach to religion and because Western culture lacks definite standards when it comes to spiritual beliefs, pluralism is the overarching standard. Man’s future hope transformed from biblical eschatology to secular utopianism. However, the industrial revolution had the effect of separating work and home life and collaterally depersonalizing relationships. This shift has disturbing moral ramifications as well.

Newbigin argues that modern society has erected a barrier between facts and values in such a way that “value free facts” are paradoxically most valued. As a result, the ascendancy of science inadvertently undermined the basis for morality. The philosopher David Hume is famous for pointing out that it is not possible to derive an “ought” from an “is.”[4] The modern scientific insistence on “what is” undercuts the basis for what is ultimate and purposeful or “what ought to be,” the focus of religion. Furthermore, he boldly suggests that the autonomy of the individual could indeed be a deception in light of God’s purpose, “That every human being is made to glorify God and enjoy him forever.”[5] It comes back around to God’s revealed truth.

In the third chapter “the Word in the World,” Newbigin examines how the western worldview has affected theology and biblical scholarship. While intending to preserve Christianity by scholarly modernization, many compromised its veracity. The fact-value divide resulted in a compartmentalization of faith as seen in the theology of Schleiermacher. Similarly, biblical scholars like Bultmann followed the dictates of naturalism to demythologize scripture. Newbigin argues correctly that we all approach the Bible with preunderstandings, and unavoidable fact which is traditionally visualized in the model of the hermeneutic circle. In the case of a believer, the text affects the interpreter modifying preunderstandings allowing a fresh look the next time around. A textbook explains it is better envisioned as a spiral, “The interpreter does not merely go around in circles. Not a vicious circle, this is, rather, a progressive spiral of development.”[6] But this only works on one who is in submission to its authority.

This brings the title of the book into focus and frames Paul’s caveat concerning the foolishness of God and the reason of man in sharp relief (1 Co 1:25). Does this render the Gospel unintelligible to the modern mind? Or perhaps it is better to say it magnifies grace? A particularly interesting point about Kuhn’s paradigm shifts is that while new paradigm may seem unintelligible from within its predecessor, once the new paradigm is adopted the old one is still accessible. An analogy between Newtonian and Einsteinian physics illustrates this point. Modern physics is unintelligible in Newtonian terms but Newtonian physics is still useful for moderns. This analogy applies in the objective manner that converts are able to evaluate their pre-Christian understandings. Even so, true progress from within the paradigm of unbelief takes divine intervention. Newbigin argues that converts “are not those who have been able to make a sort of gigantic hermeneutical leap but those who have been chosen and called-not of their own will-to be the witnesses of Jesus to the world.”[7] The circle analogy breaks down in the case of the secular unbelieving world. The secular world banks on science rather than revelation.

Science is the chief contributor to the so-called “facts” segment of the modern fact / value dichotomy. While facts are presented as value free, in reality science is not insulated from value judgments. A major strength is the book’s critique of scientism by arguing that in its reductionism, science divorces the concept purpose from nature resulting in absurdities. For example, it would be manifestly absurd to say we understand a machine in mere terms of its components without knowing its intended use. Furthermore, Newbigin argues science trades on Christian presuppositions like a rationally intelligible and contingent universe. However, given naturalism, these need not be the case. In this way, atheistic scientists exhibit a curious cognitive dissonance by borrowing from Christianity while simultaneously denying it. Consequently, Christians can function as missionaries of rationality amongst the growing unreason of reductionist absurdity. Whereas the discussion of science is perhaps the strongest of the book, the area of human action in the political sphere is less compelling.

Newbigin speaks of the historical “corpus Christianum” seemingly referring to the Holy Roman Empire as a time when society was governed by the Christian revelation. While it has some superficial truth, it seems a little too charitable, as most people were illiterate and the scriptures were largely under the magisterial thumb of the monolithic Roman church. The term “Christendom” is arguably a misnomer. Newbigin ostensibly minimizes the necessity of the reformation. It was the Protestant reformation that actually restored the Gospel and the subsequent freedom made the enlightenment and science possible. While arguing the church cannot completely abandon the temporal realm, he allows that, “the total identification of a political goal with the will of God, always unleashes demonic powers.”[8] Although he cites Islam as an example, the medieval and counter-reformation papists were no better. Moving forward, he associates capitalism with covetousness and the “Moral Majority” with idolatrous nationalism. While the former has force as seen in recent economic events, the latter might be more reflective of a European conceit. Even so, Europe is in deeper financial and moral chaos today than it was in 1986 when Newbigin wrote. In the final chapter, he argues the church must try to put the Gospel into the center of national life.

He lists seven essentials for the churches recovery of its distinction from and responsibility to secular culture: 1) a true doctrine of eschatology; 2) a Christian doctrine of freedom; 3) a “declericalized” or lay theology; 4) a critique of denominationalism; 5) seeing our own culture through Christians from other cultures; 6) to proclaim a belief that cannot be proven by cultural axioms; 7) supernatural reality is reflected in praising God. While these suggestions are basically good and certainly well intended, not all of them seem feasible and perhaps some are not all together sound.

First, his discussion of eschatology is on mostly individual terms. However, overarching millennial views profoundly affect the other points in irreconcilable ways. For example, a premillennialist is not going to share the ecumenical and moral optimism of a postmillennialist. Second, his criticism of freedom and personal autonomy is well argued and biblically sound. Believers should counter-culturally offer their lives as a living sacrifice (Rom 12:1-2). Third, a coherent lay theology sounds good on paper but suffers the same fate as his (fourth) hope for ecumenism, it seems naïve. Sincere believers disagree on important theological distinctives like Baptism and biblical inerrancy. The World Council of Churches has arguably proven to be more of the “world” than of churches. Accordingly, his ambition “to restore the face of the Catholic Church,”[9] seems like wishful thinking. In truth, the reformers ultimately came to the conclusion that Rome was hopeless. In stalwart agreement, the Church of Rome is no longer in need of reform, rather conversion. Still, there is much to be commended in this book.

Fifth, one of his most powerful suggestions is to get perspectives from other cultures. This missionary perspective is a major strength of the book. It is not very probable to get an unbiased assessment from within. For instance, his assessment of covetousness fueled capitalism not being coherent to biblical principles has force. Sixth, the suggestion to boldly proclaim that which is seen as foolishness is well taken. Radical conversion by faith in the Gospel is necessary and the only absolute external proof is eschatological. Seven, praise is what God deserves and flows from the hearts of all true blood bought believers. It is perhaps the greatest means of ecumenism as it unites believers and sends a message to the world. Ultimately, God empowers the mission and God gets the glory. In this way, the first point seems the most promising in that the problems of culture, politics, and economics are not likely to be solved by ecumenism or better theological formulations. Politically the monarchist position seems best. The return of the King of Kings is the eternal solution to the world’s political challenges.

This review offered a summary and analysis of Foolishness to Greeks. After offering a brief summary, the paper sought to illustrate the value of the book in its explanation of the modern worldview and its critique of science and the fact-value dichotomy. While criticism was offered in that the authors’ ecumenism and politics seem somewhat naïve, his assessment of science and missionary perspective are strengths. It was agreed that the church is most powerful in prayer and worship and its greatest hope is eschatological. The relationship between these points was shown. In the end, it seems that these points support the idea that the book is a valuable tool in contextualizing the Gospel for the Western mindset.

[1] Lesslie Newbigin, Foolishness to the Greeks: the Gospel and Western Culture. Kindle Edition. (Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1986) Kindle Locations 33-34.

[2] Newbigin, Foolishness, Kindle Location 59.

[3] Newbigin, Foolishness, Kindle Locations 292-293.

[4] David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature, (Sioux Falls, SD: NuVision Publications, 2007) 335.

[5] Newbigin, Foolishness, Kindle Locations 499-500.

[6] William W. Klein, Craig Blomberg, Robert L. Hubbard and Kermit Allen Ecklebarger, Introduction to Biblical Interpretation (Dallas: Word Publishers, 1993), 166.

[7] Newbigin, Foolishness, Kindle Locations 695-697.

[8] Newbigin, Foolishness, Kindle Locations 1486-1487.

[9] Newbigin, Foolishness, Kindle Location 1872.

Issues Etc & the Whitewashing of Protestant History

By Cris D. Putnam

I just listened to a “back and forth” on Issues Etc. a Lutheran radio show that I generally like for its discussion of apologetics and theology. They had Dr. Thomas Ice on talking about “Rapture Theology” and then a follow up response by Dr Kim Riddlebarger Responding to Dr Thomas Ice’s Rapture Theology. While I identify as a progressive dispensationalist, I do not really want to debate the timing of the rapture rather the strawman representation of premillennialism and complete white washing of classic Lutheran eschatology displayed by the host of Issues Etc. and Riddlebarger. One of the major objections to dispensationalism was that it was relatively new development of the nineteenth century whereas the Amillennial view was the classic protestant view. This is a drastic oversimplification of the Lutheran and Reformed positions.

I just listened to a “back and forth” on Issues Etc. a Lutheran radio show that I generally like for its discussion of apologetics and theology. They had Dr. Thomas Ice on talking about “Rapture Theology” and then a follow up response by Dr Kim Riddlebarger Responding to Dr Thomas Ice’s Rapture Theology. While I identify as a progressive dispensationalist, I do not really want to debate the timing of the rapture rather the strawman representation of premillennialism and complete white washing of classic Lutheran eschatology displayed by the host of Issues Etc. and Riddlebarger. One of the major objections to dispensationalism was that it was relatively new development of the nineteenth century whereas the Amillennial view was the classic protestant view. This is a drastic oversimplification of the Lutheran and Reformed positions.

In truth, Historicism was a foundational interpretation of Protestantism and it is perplexing that it is so flippantly forgotten. They completely ignore the subversion of Biblical doctrine by the Roman Catholic Church and the fact that many early Fathers were Premillennial. Even worse, the host and Riddlebarger made sport of premillennialists for speculating on current events in Israel as prophetically significant while ignoring the Historicist view (see p1 p2 p3 ) of the reformed tradition’s tendency to do the same. In fact, far from demuring to speak to current events, classic Protestantism has affirmed that the Great Tribulation as an ongoing reality along with the judgements of the book of Revelation. In the recent past Protestants did not speculate about the identity of Antichrist, they claimed sure knowledge. It is in all of the creeds!

Despite political correctness and its nearly forgotten status in modern evangelicalism, almost all of the original protestant confessions affirm that the papacy is antichrist. For example, The Second Scotch Confession of AD 1580 states:

And theirfoir we abhorre and detest all contrare Religion and Doctrine; but chiefly all kynde of Papistrie in generall and particular headis, even as they ar now damned and confuted by the word of God and kirk of Scotland. But in special, we detest and refuse the usurped authoritie of that Romane Antichrist upon the scriptures of God, upon the Kirk, the civill Magistrate, and consciences of men.[1]

Similarly, The Westminster Confession of Faith does not mince words concerning the papacy:

There is no other head of the Church but the Lord Jesus Christ.Nor can the Pope of Rome, in any sense, be head thereof: but is that Antichrist, that man of sin, and son of perdition, that exalteth himself, in the Church, against Christ and all that is called God.[2]

This statement was repeated virtually verbatim in the Baptist Confession of 1688, otherwise known as the Philadelphia Confession. It was the most generally accepted confession of the Regular or Calvinistic Baptists in England and in the American south. The Westminster confession is still widely used today.

While many modern Lutherans seek to distance themselves from it, The Book of Concord still contains the Smalcald Articles and the Treatise on the Primacy of the Pope. Accordingly, many orthodox Lutherans still affirm the veracity of those documents. However, in the 1860s the Iowa Synod refused to grant doctrinal status to the teaching that the Papacy is the Antichrist. They listed this teaching under the category of “open questions.” The Iowa Synod later became part of the American Lutheran Church, and its teaching on the Antichrist persisted in the new union. Since 1930, the ALC taught that it is only a “historical judgment” that the Papacy is the Antichrist. In 1938, this view was officially sanctioned in the ALC “Sandusky Declaration.” It stated:

We accept the historical judgment of Luther in the Smalcald Articles…that the Pope is the Antichrist…because among all the antichristian manifestations in the history of the world and the Church that lie behind us in the past there is none that fits the description given in 2 Thess. 2 better than the Papacy…

The answer to the question whether in the future that is still before us, prior to the return of Christ, a special unfolding and a personal concentration of the antichristian power already present now, and thus a still more comprehensive fulfillment of 2 Thess. 2 may occur, we leave to the Lord and Ruler of Church and world history.[3]

In a sharp rebuttal, the Missouri Synod’s “Brief Statement” of 1932 renounced the teaching that the identification of the papacy as the Antichrist is only a historical judgment. It professed, “The prophecies of the Holy Scriptures concerning the Antichrist…have been fulfilled in the Pope of Rome and his dominion.” It subscribed, “to the statement of our Confessions that the Pope is ‘the very Antichrist.’” It argued that the doctrine of Antichrist is “not to be included in the number of open questions.”[4] However, their position has softened since.

In 1951, the Report of the Advisory Committee on Doctrine and Practice of the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod stated:

Scripture does not teach that the Pope is the Antichrist. It teaches that there will be an Antichrist (prophecy). We identify the Antichrist as the Papacy. This is an historical judgment based on Scripture. The early Christians could not have identified the Antichrist as we do. If there were a clearly expressed teaching of Scripture, they must have been able to do so. Therefore the quotation from Lehre und Wehre [in 1904 by Dr. Stoeckhardt which identifies the Papacy as Antichrist] goes too far.[5]

This view was endorsed at the Missouri Synod Convention in Houston in 1953. Even so, many still struggle with their traditions. A Lutheran scholar, Charles Arand, wrote an article to help contemporary Lutheran’s deal with the cognitive dissonance they feel when they want to applaud the pope’s position against abortion and other moral issues. While he never denies the classic Lutheran position, he claims, “The identification of the papacy as the Antichrist in the Confessions takes place in an apocalyptic climate in which the Reformers also considered other candidates for the title of Antichrist, the most prominent of which were the Turks (Ap XV, 18).”[6] The text he refers to is this one: “For the kingdom of the Antichrist is a new kind of worship of God, devised by human authority in opposition to Christ, just as the kingdom of Mohammed has religious rites and works, through which it seeks to be justified before God.”[7]

Indeed, one could infer a Muslim antichrist from this one statement. But, in truth, his use of this reference is obfuscation because the very next sentences in Apology of the Augsburg Confession XV, 18 say:

It does not hold that people are freely justified by faith on account of Christ. So also the papacy will be a part of the kingdom of the Antichrist if it defends human rites as justifying. For they deprive Christ of his honor when they teach that we are not freely justified on account of Christ through faith but through such rites, and especially when they teach that such rites are not only useful for justification but even necessary.[8]

This issue of elevating their rites above the salvific power of the Gospel has never been recanted by the Church of Rome. He goes on to argue that as part of the “already but not yet” paradigm, the papacy was a manifestation of Antichrist during the time of the reformation but not necessarily the ultimate one. Nevertheless, this confession clearly says they will be a part of Antichrist’s kingdom. He maintains to be dogmatic that the papacy is the only antichrist precludes awareness and vigilance toward new manifestations, yet to relativize the confessions as only historical is equally an error.[9] So contrary to views expressed on the recent Issues Etc, dispensationlism did not amend their anemic modernized view rather hard-line Historicism.

It is a demonstrable historical fact that every notable protestant theologian of the 16 -19th century, regardless of denomination, believed and taught that the papacy was antichrist.

For a cogent Defense of premillennialism I recommend John MacArthur’s series here.

[1] The Second Scotch Confession in Philip Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom, Volume III (Joseph Kreifels), 349.

[2] Morton H. Smith, Westminster Confession of Faith (Greenville SC: Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary Press, 1996), 2.

[3] “Statement on the Antichrist,” Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod, last accessed January 18, 2011, http://www.wels.net/about-wels/doctrinal-statements/antichrist?page=0,1.

[4] Ibid.

[5]Ibid.

[6] Charles P. Arand, “Antichrist: The Lutheran Confessions on the Papacy,” Concordia Journal (October 2003), 402.

[7] Philip Melanchthon, Apology of the Augsburg Confession XV,18 in Robert Kolb, Timothy J. Wengert and Charles P. Arand, The Book of Concord : The Confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2000), 225.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Charles P. Arand “Antichrist: The Lutheran Confessions on the Papacy,” 403.

Hoagland & Bara’s Dark Nonsense

By Cris D. Putnam

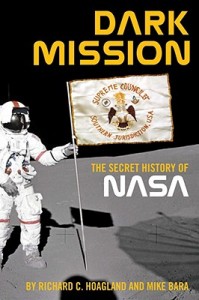

In researching various paranormal and UFO lore, I recently came across Dark Mission by Richard C. Hoagland and Mike Bara. In the book the authors make a case for an occult agenda behind NASA. According to the authors, Dr. Farouk El-Baz, an Egyptian geologist working at NASA helped high ranking freemasons land on the moon on July 20th, the date of the Egyptian New Year, to perform an arcane Egyptian rite to invoke Osiris. While the evidence of high ranking NASA officials and astronauts having masonic ties is strong, the so called ritual they expose is nothing dark at all. I personally saw the masonic flag which was taken to the moon during my recent tour of the Hall of the Temple. Sure it is possible there was a masonic agenda afoot but the incoherence of a crucial element of their thesis makes the entire account seem fanciful. Their argument centers on Buzz Aldrin’s taking of communion in the lunar module, described by Aldrin in his book Men From Earth:

In researching various paranormal and UFO lore, I recently came across Dark Mission by Richard C. Hoagland and Mike Bara. In the book the authors make a case for an occult agenda behind NASA. According to the authors, Dr. Farouk El-Baz, an Egyptian geologist working at NASA helped high ranking freemasons land on the moon on July 20th, the date of the Egyptian New Year, to perform an arcane Egyptian rite to invoke Osiris. While the evidence of high ranking NASA officials and astronauts having masonic ties is strong, the so called ritual they expose is nothing dark at all. I personally saw the masonic flag which was taken to the moon during my recent tour of the Hall of the Temple. Sure it is possible there was a masonic agenda afoot but the incoherence of a crucial element of their thesis makes the entire account seem fanciful. Their argument centers on Buzz Aldrin’s taking of communion in the lunar module, described by Aldrin in his book Men From Earth:

During the first idle moment in the LM before eating our snack, I reached into my personal preference kit and pulled out two small packages which had been specially prepared at my request. One contained a small amount of wine, the other a small wafer. With them and a small chalice from the kit, I took communion on the Moon, reading to myself from a small card I carried on which I had written the portion of the Book of John used in the traditional communion ceremony.[1]

Sounds awfully scary doesn’t it? Dark Mission makes the dubious leap of asserting that Aldrin’s intent was not to worship Jesus Christ but to preform some sort of nefarious Masonic ritual based on Egyptian magic.

Hoagland next discovered that Aldrin’s ceremony (which was taken from Webster Presbyterian Church rituals, in Houston, which, in turn, “borrowed” it from the much older Catholic communion ceremony), in fact, had its real roots in ancient Egypt— as an offering to Osiris (naturally). [2]

This is a radical assertion! Egypt is juxtaposed against Israel in the biblical narrative. From Moses’ showdown with Pharaoh’s magicians forward, the Egyptian deities are represented as antagonists to Yahweh. Yet, the authors brazenly assert that a major sacrament of a two thousand year old religion is really an offering to a hostile god while providing no scholarly documentation and expect the reader to simply accept it? Most astonishing, the allegation that the communion ceremony has “its real roots in Egypt as an offering to Osiris” is merely footnoted with a wikipedia article on Osiris. The footnoted article makes no such connection. Looking at the wiki article on 5/20/2012, the word “communion” is not even mentioned. What a joke! This radical assertion at least requires a coherent argument and historical documentation. But neither is forthcoming. The closest thing to evidence comes later:

Once again, it was Ken Johnston who provided a key insight. After discussing with Johnston the now infamous “communion ceremony that Aldrin had conducted, Ken pointed out that Aldrin—like Johnston himself—had at the time been a 32o Scottish Rite Freemason. He also noted that a recent book by two Masonic scholars (Christopher Knight and Robert Lomas) had concluded that virtually all of the Masonic rituals were derived from the story of Isis and Osiris. [3]

It’s hard to fathom why anyone would find this compelling. This argument is what logicians call a non-sequitur meaning it “does not follow.” Hoagland and Bara’s reasoning is that 1) Aldrin took communion; 2) Aldrin was a freemason 3) Most Freemasonic rituals are derived from Osiris lore; therefore communion is an Egyptian Osiris ritual. I suppose if a freemason puts his hand on his heart while singing the National Anthem then that too is a form of Osiris worship? It does not follow.

The fact that Aldrin was a mason says nothing about Christian communion. Freemasonry advocates a form of pluralism that accepts members of any religion. Does that make the practices of Islam and Hinduism also derivative of Egyptian Osiris worship? Of course not, this sort of incoherent reasoning is ubiquitous in Dark Mission. It seems they pulled most of their alleged Egyptian connections from one single poorly supported piece of pseudo-historical research called the The Hiram Key.

Their book The Hiram Key showed that, contrary to Masonry’s own lore, the Craft was not found

ed in London in 1717, but in fact traced its roots all the way back to ancient Egypt. They followed a trail back through time, to the Templars, to Jesus and the Temple of Jerusalem, then on to the builder of the first Temple of Solomon, Hiram Abiff. They concluded that the ritual of the third-degree of Freemasonry was a re-enactment of Abiff’s murder for refusing to reveal the high secret of the Craft, and that this same ritual was in fact derived from the ancient Pharaohaic rituals that paid direct homage to Isis and Osiris. They also asserted that Jesus himself was an initiate of this quasi-Masonic order, and that his real teachings had been usurped and distorted by the Catholic Church millennia before. They viewed Jesus as a martyred prophet, but not a divine being as the Church came to ultimately insist. None of this made them very popular with either the Christians or their own fellow Masons. [4]

Nor are they popular with scholars of ancient literature because the conclusions of The Hiram Key are not supported by historical evidence. The argument fails because we have copies of the New Testament which predate Roman Catholicism and there are no “suppressed teachings” of Jesus rather gnostic writings which appeared centuries after the canonical Gospels. The scholarship in The Hiram Key ( and collaterally Dark Mission) is, frankly, sloppy as there is a sophomoric lack of critical assessment of sources and they naively accept the use of masonic symbolism for evidence of historic facts. For instance, the connection of modern masonry to Hiram Abiff from the Old Testament is widely agreed to be concocted mythology designed to give masonry an ancient veneer. I challenge Hoagland and Bara to produce a single credentialed Ancient Near Eastern scholar who believes it. Even the Freemasons have issued rebuttals here and masonic libraries catalog The Hiram Key as a work of fiction.

As far as communion being some sort of dark ritual to Osiris, the authors never make that case. The practice predates the origin of masonry by over 1600 years and has nothing to do with Osiris. According to Erickson, “It may be defined, in preliminary fashion, as a rite Christ himself established for the church to practice as a commemoration of his death.”[5] Indeed, communion was instituted by Jesus (Matt. 26:26–28; Mark 14:22–24; Luke 22:19–20). The earliest extant written account of a Christian eucharistia which is simply Greek for “thanksgiving” is that in the First Epistle to the Corinthians (dated around AD 55), in which the Apostle Paul relates the celebration to the Last Supper of Jesus some 25 years earlier (1 Co 11:23–29).

Paul argues that in celebrating the commemoratory rite they were fulfilling a mandate by Jesus to do so. The book of Acts (dated prior to AD 70) also presents the early Christians as meeting for “the breaking of bread” as some sort of ceremony (Acts 2:46). Also other very early writings like the Didache,1 Clement and Ignatius of Antioch provide examples of the thanksgiving sacrament. In the second century, Justin Martyr gives the oldest explicit description of the ceremony. In fact, Justin specifically refutes any connection to paganism when he refutes the Mithra cult who were copying the Christians!

Which the wicked devils have imitated in the mysteries of Mithras, commanding the same thing to be done. For, that bread and a cup of water are placed with certain incantations in the mystic rites of one who is being initiated, you either know or can learn. [6]

In the tradition of Justin, I argue that if freemasons have adopted communion as a masonic ritual then the same charge applies. Hence the burden of proof is on Hoagland and Bara to show evidence predating the first century which connects Jesus and the communion rite to Osiris. Of course, there is no such evidence. Hoagland and Bara admit their entire case is based on the dubious work The Hiram Key:

If Knight and Lomas were right, then Aldrin’s communion ceremony had no conventional Christian significance at all; it was, in fact, a direct offering by a Freemason to “the ancient Egyptian gods” that his Craft most revered. (underline added)[7]

But if Knight and Lomas are wrong, then Hoagland and Bara’s Dark Mission is a work of dark nonsense.

[1] Buzz Aldrin and Malcolm McConnell, Men from Earth (New York: Bantam, 1989), 248.

[2] Richard C. Hoagland and Michael Bara, Dark Mission: the Secret History of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Port Townsend, Wash.: Feral House, 2007), 207-208.

[3] Richard C. Hoagland and Michael Bara, Dark Mission, 222.

[4] Richard C. Hoagland and Michael Bara, Dark Mission, 223.

[5] Millard J. Erickson, Christian Theology, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Book House, 1998), 1116.

[6] Justin Martyr, First Apology ; chapter 66 Of the Eucharist. http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/justinmartyr-firstapology.html

[7] Richard C. Hoagland and Michael Bara, Dark Mission, 223.