By Cris D. Putnam

Do miracles prove God or does the existence of God prove that miracles happen? What place do miracles have in apologetics? In discussing miracles, the “value project” is a discussion of the evidential merits of miracles. This can be subdivided into the “basis” question which looks at the evidence that miracles have indeed occurred and the “use” question which asks what religious beliefs are supported by said basis. There are two principle approaches to addressing the value project: the bottom-up approach and the top-down approach. While there are winsome and compelling advocates of both approaches in Christian apologetics, this essay will argue the case that the latter, the top-down, is preferable.

Do miracles prove God or does the existence of God prove that miracles happen? What place do miracles have in apologetics? In discussing miracles, the “value project” is a discussion of the evidential merits of miracles. This can be subdivided into the “basis” question which looks at the evidence that miracles have indeed occurred and the “use” question which asks what religious beliefs are supported by said basis. There are two principle approaches to addressing the value project: the bottom-up approach and the top-down approach. While there are winsome and compelling advocates of both approaches in Christian apologetics, this essay will argue the case that the latter, the top-down, is preferable.

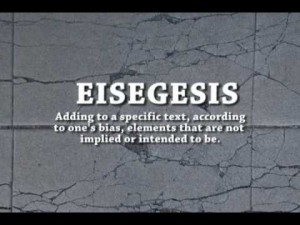

The bottom-up approach (miracles prove God) argues from the occurrence of miracles to God’s existence. This approach uses various forms of evidence as a basis to believe in miracles. For instance, the historical evidence for Jesus resurrection is well attested and represents an event that does not conform to natural laws. Because there are no coherent natural explanations it follows that it must have been a miracle. The “use project” argues from this basis that we have a reason to believe that God exists. Skeptics invariably dispute the historical evidence and offer up naturalistic explanations like the “swoon theory” and legendary development for why people came to believe it. The resurrection is one of the arguments employed by William Lane Craig for God’s existence.

Craig employs this evidence as an argument for God’s existence. However, it is important to note that he does not use this approach alone but in conjunction with the cosmological and moral arguments for a cumulative argument. In this way, his comprehensive approach is effectively top-down.

The top-down approach argues for the occurrence of miracles based on the existence of God. Philosopher Alvin Plantiga argues that one can assume theism as a properly basic belief. A properly basic belief does not depend upon justification of other beliefs, but on something outside the realm of belief. For instance we simply assume that other people are like ourselves as conscious rational beings rather than zombie like automatons merely posing. We do not need fancy philosophical arguments to believe we exist and that other minds exist. Thus, Plantinga argues, “if believing in other minds is rational though unsupported by argument, so might believing in God be rational, even if similarly unsupported.”[1] In other words, we have rational warrant to accept God’s existence as foundational. It is also important to note that the Bible simply assumes the existence of God as the basis for creation. It seems best we model our approach on the Bible.

Even so, we can still offer evidential arguments that strongly support theism. The fine tuning of the Universe and Big bang cosmology which demands that the Universe began to exist give the cosmological argument force. The top-down method starts with independent reasons for God’s existence like the existence of moral values and even reason itself (laws of logic) also evidence the handiwork and mind of God. Albert Einstein once marveled, “The most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible.”[2] It is not merely the fact that that the universe is intelligible that is amazing, rather it is the mathematical nature of that comprehensibility which is even more miraculous. Oxford mathematician and philosopher of science John Lennox writes:

Our answer to the question of why the universe is rationally intelligible will in fact depend, not on whether we are scientists or not, but on whether we are theists or naturalists. Theists will say that the intelligibility of the universe is grounded in the nature of the ultimate rationality of God: both the real world and the mathematics are traceable to the Mind of God who created both the universe and the human mind. It is therefore, not surprising when the mathematical theories spun by human minds created in the image of God’s Mind, find ready application in a universe whose architect was that same creative mind.[3]

It appears that discovered immaterial realities like mathematics and the laws of logic give us very compelling warrant to believe in God. The Bible also confirms that the “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom; all those who practice it have a good understanding. His praise endures forever!”(Ps 111:10). Thus, a top-down approach is preferable. Because we believe in God, we think miracles are plausible.

Because we have such strong warrant to believe God exists, we are justified to believe that He would want to get a message to us and provide a means for our redemption and spiritual growth. Jesus’ resurrection did not happen in a vacuum but rather in the context of His claim to be the Jewish Messiah and the Son of God. One can also trace a stream of predictive prophecy through the Old Testament supporting his mission and resurrection (e.g. Isaiah 53). Furthermore, the evidence of biblical prophecy serves to authenticate the inspiration of the Bible as God’s word. With the foundational premise that God exists then there is no need to repeatedly address naturalistic prejudice against the historical evidence for miracles. In light of the ample warrant for God’s existence and the context of Jesus’ life and ministry, the likelihood of a miracle is much more compelling than with a strictly bottom-up argument. The existence of the God of the Bible provides a rational basis to believe miracles happen.

[1] Alvin Plantinga, God and Other Minds: a Study of the Rational Justification of Belief in God (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1990), 187 ff.

[2] Albert Einstein, Letters to Soloivine: 1906-1955 (Yucca Valley: Citadel Publishing. 2000), 31.

[3] John C. Lennox, God’s Undertaker: Has Science Buried God? (Oxford: Lion Publishing, 2007), 61.