As presented in my previous post, the conflation of Mark 13, Matthew 24 and Luke 21 as a single teaching by Jesus is a popular misconception amongst scholars. Preterists typically presume higher critical source theories which demand that Matthew and Luke copied Mark and another document (never proven to exist) called Q. Classically the church positioned Matthew as the first gospel which is why it appears first in our Bibles. This finds support in the fact that Eusebius quotes the testimony of Papias who wrote that Matthew had collected Jesus oracles in Hebrew. As a tax collector, Matthew would have been trained in shorthand and able to record Jesus words with great accuracy and speed. Preterists seek to diminish the accuracy of Matthew’s Gospel because it strains their position. For instance, in the previous post we saw that JP Holding believes that Matthew is using hyperbole for dramatic effect in Mt. 24:21 and the text does not really mean what it actually says (only because its a huge problem for preterism). This is special pleading of the worst kind. There is no exegetical warrant not to take the text at face value. While asserting hyperbole might work for the apocalyptic genre, Matthew 24 is a teaching discourse. Jesus is answering a question, it is not apocalyptic literature. While Mark and Matthew certainly share material, Luke rather obviously represents a different teaching in response to a different question. First, let’s try to better understand the preterist’s position.

As presented in my previous post, the conflation of Mark 13, Matthew 24 and Luke 21 as a single teaching by Jesus is a popular misconception amongst scholars. Preterists typically presume higher critical source theories which demand that Matthew and Luke copied Mark and another document (never proven to exist) called Q. Classically the church positioned Matthew as the first gospel which is why it appears first in our Bibles. This finds support in the fact that Eusebius quotes the testimony of Papias who wrote that Matthew had collected Jesus oracles in Hebrew. As a tax collector, Matthew would have been trained in shorthand and able to record Jesus words with great accuracy and speed. Preterists seek to diminish the accuracy of Matthew’s Gospel because it strains their position. For instance, in the previous post we saw that JP Holding believes that Matthew is using hyperbole for dramatic effect in Mt. 24:21 and the text does not really mean what it actually says (only because its a huge problem for preterism). This is special pleading of the worst kind. There is no exegetical warrant not to take the text at face value. While asserting hyperbole might work for the apocalyptic genre, Matthew 24 is a teaching discourse. Jesus is answering a question, it is not apocalyptic literature. While Mark and Matthew certainly share material, Luke rather obviously represents a different teaching in response to a different question. First, let’s try to better understand the preterist’s position.

Some scholars believe that Matthew 24 and Luke 21 are the same discourse arranged differently by the evangelist authors Matthew and Luke. This sort of thinking explains why the parables are placed in varying contexts and why the Gospels have chronological differences. It explains what is known as the synoptic problem. Thus, it is appropriate to recoginize that there are layers of context in the Gospels. For instance, scholars explain the various iterations of Jesus’ sayings in this way:

It should not surprise us, therefore, to learn that many such sayings (without contexts) were available to the evangelists, and that it was the evangelists themselves, under their own guidance of the Spirit, who put the sayings in their present contexts. This is one of the reasons we often find the same saying or teaching in different contexts in the four gospels—and also why sayings with similar themes or the same subject matter are often grouped in a topical way.[1]

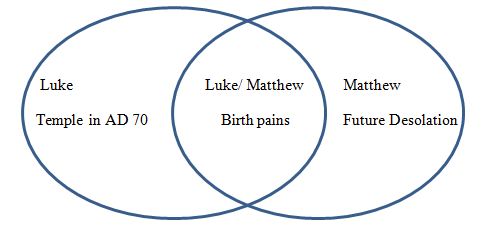

While acknowledging that this explains some instances of repeated material in the Gospels, it also seems fair to argue that because Jesus was a traveling preacher, he repeated his material in each location he visited. In other words, one would expect certain teachings to be repeated in different contexts. That being the case, one would also expect His sayings to be recorded by eyewitnesses in overlapping ways. The question we need to ask ourselves is, is this simply the authors Matthew and Luke molding the same teaching to his own particular context or are these two different teachings by Jesus. I believe careful exegesis reveals that the similarities between Luke 21 and Matthew 24 are superficial and simply reflect Jesus teaching a few of the same concepts (like the birth pains) in different contexts.

The text of Luke 21 and Matthew 24 are not simply different hearings of the same teaching rather they are answering two different questions using some overlapping material. This is evident from four lines of evidence. First, Matthew’s discourse was private to disciples on the Mount of Olives (Mt 24:3), whereas Luke’s was a public teaching at the temple (Lk 21:1). The two teachings are clearly set at different locations:

| Matthew | Luke |

| “As he sat on the Mount of Olives, the disciples came to him privately… ” (Mt 24:3a) | “One day, as Jesus was teaching the people in the temple and preaching the gospel…(Lk 20:1a) “Jesus looked up and saw the rich putting their gifts into the offering box,”(Lk 21:1) |

Second, while the answers are very similar, Jesus is actually answering a different question in Luke and Matthew. In Luke, they are asking him about the destruction of the temple (Lk 21:7) but in Matthew they privately ask him about the end of the age and his return (Mt 24:3). Luke is public teaching concerning the destruction of the temple but Matthew is a private teaching about the end times. This is easily discerned by anyone willing to examine the text:

| Matthew | Luke |

| “As he sat on the Mount of Olives, the disciples came to him privately, saying, “Tell us, when will these things be, and what will be the sign of your coming and of the end of the age?”(Mt 24:3) | “As for these things that you see, the days will come when there will not be left here one stone upon another that will not be thrown down.” And they asked him, “Teacher, when will these things be, and what will be the sign when these things are about to take place?”(Lk 21:6–7) |

Third, Jesus makes them distinct temporally. This is where preterists tend to get confused but it’s really not too hard. In both Matthew and Luke, Jesus lists a series of birth pains (Mt 24:6-8 c.f. Lk 21:10-12). However, Matthew follows the list with “Then (after) they will deliver…” (v.9). Because this distinction is crucial exegetically let’s examine the passages in question in their original Greek and consult the Louw Nida Lexicon:

9 Τότε παραδώσουσιν ὑμᾶς εἰς θλῖψιν καὶ ἀποκτενοῦσιν ὑμᾶς, καὶ ἔσεσθε μισούμενοι ὑπὸ πάντων τῶν ἐθνῶν διὰ τὸ ὄνομά μου. (Mt 24:9, NA27)

67.47 τότε; κἀκεῖθενb: a point of time subsequent to another point of time—‘then.’[2]

However, Luke follows the birth pains with “But before all of this…” (v.12).

12 Πρὸ δὲ τούτων πάντων ἐπιβαλοῦσιν ἐφʼ ὑμᾶς τὰς χεῖρας αὐτῶν καὶ διώξουσιν, παραδιδόντες εἰς τὰς συναγωγὰς καὶ φυλακάς, ἀπαγομένους ἐπὶ βασιλεῖς καὶ ἡγεμόνας ἕνεκεν τοῦ ὀνόματός μου,”(Lk 21:12, NA27)

67.17 πρόb; πρίν or πρὶν ἤ; ἄχρι οὗa: a point of time prior to another point of time—‘before, previous.’[3]

Accordingly, the instructions in Luke are prior to the birth pains ( e.g. A.D. 70) directed to contemporary Christians in Jerusalem whereas Matthew’s instructions are for after the birth pains, arguably still future. The texts overlap but they are not the same!

| Matthew | Luke |

| “Then they will deliver you up to tribulation and put you to death, and you will be hated by all nations for my name’s sake.”(Mt 24:9) | “But before all this they will lay their hands on you and persecute you, delivering you up to the synagogues and prisons, and you will be brought before kings and governors for my name’s sake.”(Lk 21:12) |

Fourth, in Luke, the instruction is to flee Jerusalem when armies surround it (Lk 21:20) Yet, in Matthew and Mark, the instruction is to flee when the abomination of desolation takes place (Mt 24:15; Mk 13:14).

| Matthew | Luke |

| “So when you see the abomination of desolation spoken of by the prophet Daniel, standing in the holy place (let the reader understand),” (Mt 24:15) | ““But when you see Jerusalem surrounded by armies, then know that its desolation has come near.(Lk 21:20) |

It seems that careful exegesis leads to the conclusion that Luke is not the private Olivet discourse concerning the Parousia rather a similar yet distinct public warning for first century Christians. It worked because Tertullian recorded that John and others escaped a few years prior to AD 70. Matthew 24, on the other hand, describes future events just prior to Jesus return. This accounts for preterism as well as futurism and reveals why preterist eschatology is ultimately mistaken. This supports my previous post and reveals why I think preterism as an explanation for Matthew 24 is absurd.

I will be posting more in this series later…

[1] Gordon D. Fee and Douglas K. Stuart, How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth, 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1993), 132.

[2] Johannes P. Louw and Eugene Albert Nida, vol. 1, Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains, electronic ed. of the 2nd edition. (New York: United Bible Societies, 1996), 634.

[3] Ibid, 630.