By Cris D. Putnam

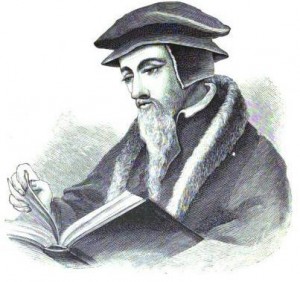

Calvin shared and affirmed Luther’s conclusions concerning the papacy. In his Institutes, he based his primary argument on the 2 Thessalonians passage and the “little horn” prophecies in Daniel, arguing that the papacy personifies arrogant displacement of the Gospel. He argues that this is so self-evident, that denying it is to dispute the Apostle Paul’s credibility:

To some we seem slanderous and petulant, when we call the Roman Pontiff Antichrist. But those who think so perceive not that they are bringing a charge of intemperance against Paul, after whom we speak, nay, in whose very words we speak. But lest anyone object that Paul’s words have a different meaning, and are wrested by us against the Roman Pontiff, I will briefly show that they can only be understood of the Papacy.[1]

He contends that the worldly pope sits in opposition to the spiritual kingdom of Christ. Based on the “mystery of inequity already at work” he denies that it could be, “introduced by one man, nor to terminate in one man.” [2] Searching the Institutes for the terms “Antichrist” and “Papacy” occurring together with Libronix software returns a total of thirty-five occurrences in seven articles. Thus, it is safe to say that the view goes hand-in-hand with historic Calvinism. A later Swiss Calvinist Theologian, Francis Turretin, is famous for his polemic style and his Seventh Disputation: Whether it Can Be Proven the Pope of Rome is the Antichrist, published in 1661, is such a foundational treatment on the subject that it will be examined in more depth.

Turretin followed in Calvin’s footsteps in Geneva where he was born and later buried. Even so, he was cut from broad cloth, educated in a variety of theological centers: Geneva, Leiden, Utrecht, Paris, Saumer, Montauban, and Nimes. He was ordained as a pastor to the Italian parishioners in Geneva in 1647; later in 1653 he became professor of theology.[3] Among his writings, his Institutio Theologiae Elencticae, a systematic theology written in argumentative form, became the standard text at Princeton Theological Seminary only until it was replaced by Charles Hodge’s Systematic Theology in the late nineteenth century. His style of elenctic theology is still studied by reformed apologists and theologians today. The point of this seventh argument in the larger work is that the seventh major reason Protestants can never be reconciled with the Roman Catholic Church is that the pope is certainly the Antichrist. This work is known as the classic apology for the papal antichrist and the Church of Rome as Mystery Babylon.

Turretin builds his case systematically from the ground up. He addresses the many ways in which the term “antichrist” may be used as was done at the beginning of this book. He establishes a semantic case that the Latin “vicar” carries a similar meaning to the Greek “anti” as “one who comes in the place of another.”[4] He makes a powerful case from 2 Thessalonians that, “The Pope takes for himself not only the name of the Church, but with its name its privileges and all authority, as if he alone (with his faithful) were the temple of God, which is the Church (the Christians outside his belief system being viewed as heretics and schismatics).”[5] He then establishes that the location, Rome, matches the prophecy in Revelation 17 incorrigibly. He argues that Babylon was a known codeword for Rome used by early Christians (cf. 1 Pe 5:13) and “the seven heads are seven mountains” (Re 17:9) infers Rome which was famously called “the City on Seven Hills.” He argues that, “the great seven-hilled city, which in John’s day held power over the kings of the earth, and which, by her cup of fornications, was destined to inebriate all people, intoxicating them with the blood of the saints” cannot represent Pagan Rome because only Christian Rome could slide into apostasy.[6]

While some of his exegesis is suspect, his reasoning is, for the most part, impeccable as he systematically builds the case. For instance, he argues Paul mentioning that the “mystery of lawlessness is already at work” (2 Th 2:7) can only describe an entity which had its roots at the onset of the Church. The Thessalonians had to know about it for Paul’s letter to be coherent. Accordingly, he reasons the restraining influence was the Roman Empire. History bears this out as the papacy assumed greater temporal power as the Empire fell. He cites examples from history of various popes asserting their power over the earth as vicars of Christ. He argues that birth and revelation of the Antichrist came to fruition in AD 606 with Boniface III who claimed the title of “Universal Bishop.”[7] Furthermore, their regalia match the descriptions in Revelation 17:3, 4 with uncanny accuracy. The Church of Rome martyred many Christian believers in accordance with Revelation 17:6, he goes on to claim. Less convincing, he even postulates that the mark of the beast is Catholic sign of the cross. At the end of his treatment, he addresses counter arguments and refutes them.

One particularly compelling counterargument is titled, “Antichrist’s Attack and Denial of Christ is Hidden and Implicit; Not Open and Explicit.” He makes the case that those who object to the papal antichrist often do so because the pope ostensibly believes in and promotes Jesus. (This sounds like many modern evangelicals today.) It seems valid because it ostensibly disagrees with John’s definition, “he who denies the Father and the Son” (1 Jn 2:22b). This is still a popular objection today, so his work is quite relevant. On opposing Christ, he says the following:

Is it to be understood as open and explicit as far as external profession, or implicit and hidden as far as the actual truth of the matter? We Reformed hold firmly that the Antichrist must deny Christ, not in the first, but in the second manner; that he must be a disguised enemy of Christ, who, under the pretence of the name of Christ would rule over the Church of Christ, attacking the person of Christ, his offices and his good works. It must not, therefore, be expected that the Antichrist would openly profess himself the enemy of Christ, (although in reality he shows himself to be such), nor would he boast himself to actually be the Christ, which the pseudo-christs did.[8]

This argument is a fine example of his elenctic style. The explanation carries some weight because only in this way can the Antichrist simultaneously meet both meanings of the prefix “anti.” If he were to openly oppose Christ, no one would accept him instead of Christ. It seems that many folks have a cartoonish image of the antichrist and false prophet figures in mind. Whether or not we accept that the papacy is antichrist this argument should give us notice that it is not likely these end time figures will be so easily identified and exposed. Indeed, according to scripture they will fool most of the people on earth. The false prophet figure is described as “like a lamb” which seems to imply he is considered a Christian (Rev 13:11).

The next post will continue to examine historic protestant views on antichrist.

[1]John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, Translation of: Institutio Christianae Religionis.; Reprint, With New Introd. Originally Published: Edinburgh: Calvin Translation Society, 1845–1846 (Bellingham, WA: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 1997), IV, vii, 25.

[2] Ibid.

[3] R. J. VanderMolen, “Francis Turretin,” as quoted in Evangelical Dictionary of Theology: Second Edition, ed. Walter A. Elwell (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2001), 1221.

[4] Turretin, Seventh Disputation: Whether it Can Be Proven the Pope of Rome is the Antichrist, trans. Kenneth Bubb (Iconbusters.com, ebook location 9.8, last accessed October 01, 2011, http://www.iconbusters.com/iconbusters/htm/catalogue/turretin.pdf.)

[5] Ibid., 21.6.

[6] Ibid., 24.3.

[7] Ibid., 42.6.

[8] Ibid., 136.2–136.9.