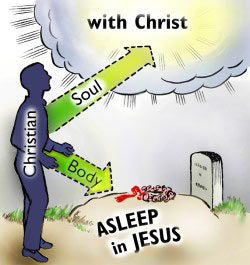

What happens when you die? The Bible uses the word death in different senses. Jesus said: “And do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul. Rather fear him who can destroy both soul and body in hell” (Mt 10:28). Also in Revelation 20:6, John speaks of a “second death,” apparently distinguishing it from the first death or the usual understanding of death. It is important to note that the only way to escape the second death and Hell is through the Lord Jesus Christ (Jn 11:26). Make sure to be in on that one! Now we turn to what happens to Christian believers at the “first death.” Paul addresses the issue of what happens to Christians when they die in 2 Corinthians 5:8 when he says “we would rather be away from the body and at home with the Lord.” This refers to the intermediate state between a believer’s death and the resurrection of all believers’ bodies at the Parousia. I have always thought that heaven is temporary state until Jesus returns for the general resurrection of the dead (Dan 12:2; Rev 20:4-6). So if you die before Christ returns, I always assumed you exist as a spirit until then. It seems to me that we consist of material and immaterial elements and in our present lives we are in a state of conditional unity. A useful analogy for conditional unity comes from chemistry.

What happens when you die? The Bible uses the word death in different senses. Jesus said: “And do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul. Rather fear him who can destroy both soul and body in hell” (Mt 10:28). Also in Revelation 20:6, John speaks of a “second death,” apparently distinguishing it from the first death or the usual understanding of death. It is important to note that the only way to escape the second death and Hell is through the Lord Jesus Christ (Jn 11:26). Make sure to be in on that one! Now we turn to what happens to Christian believers at the “first death.” Paul addresses the issue of what happens to Christians when they die in 2 Corinthians 5:8 when he says “we would rather be away from the body and at home with the Lord.” This refers to the intermediate state between a believer’s death and the resurrection of all believers’ bodies at the Parousia. I have always thought that heaven is temporary state until Jesus returns for the general resurrection of the dead (Dan 12:2; Rev 20:4-6). So if you die before Christ returns, I always assumed you exist as a spirit until then. It seems to me that we consist of material and immaterial elements and in our present lives we are in a state of conditional unity. A useful analogy for conditional unity comes from chemistry.

Did you know that every summer, including this one, thousands of people will die from dihydrogen monoxide inhalation? Yes it is true… they drown while swimming in pools, the ocean or lakes. It’s a bad joke. Dihydrogen monoxide is H20 or plain old water. Now of course we all know that water is not usually dangerous and is, in fact, essential for life. But what happens when you break water down into its two components hydrogen and oxygen? It suddenly takes on drastically different properties. In fact, it gets downright dangerous. In the presence of an oxidizer like oxygen, hydrogen can catch fire, sometimes explosively, and it burns more easily than gasoline does. According to the American National Standards Institute, hydrogen requires only one tenth as much energy to ignite as gasoline does. So when water is separated into its two elements, they are nothing like water. It seems appropriate to think of the body and soul in the same way. In life we are like a molecule consisting of body and soul. At death the material and immaterial are separated and take on different properties. The material body decays and the immaterial soul transfers into the spiritual dimension. So what does the New Testament tell us about this process?

According to some scholars, Paul does not seem to believe in a bodiless ethereal state in heaven rather an immediate transformation to a new body. F.F. Bruce thinks Paul’s view is that some sort of body is essential to personhood.[1] This is most evident in 2 Corinthians 5:1-5 where he speaks of putting on the heavenly dwelling. Paul argues that we put it on so that we will “not be found naked” (2 Cor 5:3) which likely refers to the intermediate state in which believers’ spirits are with God but they do not yet enjoy their resurrected bodies. Accordingly, Bruce argues that Paul did not envision an intermediate state as a disembodied spirit and that it is difficult to distinguish any difference between this and the glorified body believers are to receive at the Parousia (1 Cor. 15:51). He believes that Paul is teaching that believers receive their eternal resurrection bodies at death, rather than waiting for Christ to return in glory.[2]

But our citizenship is in heaven, and from it we await a Savior, the Lord Jesus Christ, who will transform our lowly body to be like his glorious body, by the power that enables him even to subject all things to himself. (Php 3:20-21)

Scholars have different views on this. Like Bruce, W. D. Davies argues, “there is no room in Paul’s theology for an intermediate state of the dead.”[3] But 1 Corinthians 15:51-53 seems to place this at the last trump – the return of Christ. The general consensus of conservative theologians seems to support an intermediate state between death and the resurrection body. Millard Erickson argues, “there is no inherent untenability about the concept of disembodied existence. The human being is capable of existing in either a materialized (bodily) or immaterialized condition.”[4] Many commentators view the 2 Corinthians 5:1 passage as Paul’s “hope of receiving the resurrection body at Christ’s return.”[5] Another view of Paul’s argument about “not being found naked” is that it was intended as a polemic against those who taught existence in a state of disembodied immortality.[6] There are passages in the Bible that seem to support the idea of a temporary disembodied soul state (Rev 6:9) but even here these tribulation martyrs put on white robes. Isaiah 14:9-10 seems to describe the disembodied souls of the dead being “stirred up.” 2 Corinthians 12:2-3 also supports the idea of existence outside of a body. I guess biggest question you have to ask is that if we get a body at death, then what is resurrection of the dead at Christ’s return for? It would no longer seem necessary (1 Thes 4:17; Rev 20:4). It seems to be tied to our old body in some way. Accordingly, there seems to be an intermediate state of some sort. A humble posture is in order as the evidence does not seem conclusive either way. Perhaps the resurrection body is granted but not fully realized until Christ’s return?

Either way the biblical teaching is clear that believers enjoy immediate fellowship with the Lord. Contrary to the teachings of Seventh Day Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses, the idea of soul sleep is not supported by the biblical text (Luke 23:43; Phil. 1:23; Heb. 12:23). This offers great comfort to the loved ones of Christians. They need not grieve as those who have no hope (1 Thes 4:13). Finally, 2 Corinthians 5:6-10 offers ample motivation for living to please God as well. We are charged to live courageously in knowledge that we will soon appear before the judgment seat of Christ when we shall give an account of our lives (Ro 14:12).

[1] F. F. Bruce, Paul: Apostle of the Heart Set Free (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1977), 311.

[2] Bruce, Paul, 312.

[3] W. D. Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism (London: SPCK, 1955), pp. 317–18.

[4] Millard J. Erickson, Christian Theology, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Book House, 1998), 1189.

[5] Thomas D. Lea and David Alan Black, The New Testament : Its Background and Message, 2nd ed. (Nashville, Tenn.: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2003), 422.

[6] Kenneth L Barker, Expositor’s Bible Commentary (Abridged) (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1994), 676.