By Cris D. Putnam (continued from part 4)

Giordano Bruno (1548–1600) is regarded among extraterrestrial apologists, secular and occult, as a free-thought martyr. Born in Naples, Bruno was a Catholic priest, Dominican monk, philosopher, hermetist, Kabbalist, mathematician, and astronomer. Influenced by Lucretius, his cosmology went well beyond the Copernican model by proposing that the sun was merely a garden variety star, and moreover, that the universe contained an infinite number of worlds populated by intelligent alien beings. Delving deeply into occult lore, Bruno preferred magical to mathematical reasoning. Bruno’s faith has been described as “an incoherent materialistic pantheism.”[1] Moreover, Bruno argued that his beliefs did not contradict Scripture or true religion. Yet, this begs the question: What did he regard as true religion?

Giordano Bruno (1548–1600) is regarded among extraterrestrial apologists, secular and occult, as a free-thought martyr. Born in Naples, Bruno was a Catholic priest, Dominican monk, philosopher, hermetist, Kabbalist, mathematician, and astronomer. Influenced by Lucretius, his cosmology went well beyond the Copernican model by proposing that the sun was merely a garden variety star, and moreover, that the universe contained an infinite number of worlds populated by intelligent alien beings. Delving deeply into occult lore, Bruno preferred magical to mathematical reasoning. Bruno’s faith has been described as “an incoherent materialistic pantheism.”[1] Moreover, Bruno argued that his beliefs did not contradict Scripture or true religion. Yet, this begs the question: What did he regard as true religion?

Bruno defined magic as “the knowledge of the science of nature.”[2] Within the renaissance worldview, it was common to merge magic and science because both explore and seek to gain mastery over the structure of the universe. Similarly, religion and magic were conflated because both answered the ultimate questions and offered communion with the divine. Accordingly, for Bruno, magic was the tool for realizing the ends of science and religion. While it seems at odds with the cold, hard, materialist posturing we are accustomed to, naturalist scientists are the heirs apparent to many of the occult traditions. Scholars have traced two streams of occultism in Bruno’s work.

Frances Yates, a scholar of Renaissance occultism, traced Bruno’s thought to the fifteenth-century rediscovery of the Hermetic Corpus, a Gnostic work allegedly authored by Hermes Trismegistus (meaning “thrice-greatest Hermes”), who is a syncretism of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. In Hermetic lore, Trismegistus is credited with having delivered all science, medicine, and magic to mankind. Yates makes the case that during the Renaissance, hermeticism spread like wildfire across the intellectual West, inspiring a revival of Egyptian magic practice and alchemy. In the case of Giordano Bruno, she writes:

Bruno was an intense religious Hermetist, a believer in the magical religion of the Egyptians as described in the Asclepius, the imminent return of which he prophesied in England, taking the Copernican sun as a portent in the sky of this imminent return. He patronises Copernicus for having understood his theory only as a mathematician, whereas he (Bruno) has seen its more profound religious and magical meanings.[3]

Bruno cobbled the atomist extraterrestrial doctrine together with Egyptian magic, creating a system all his own. Yates writes,

Thus that wonderful bound of the imagination by which Bruno extended his Copernicanism to an infinite universe peopled with innumerable worlds, all moving and animated with the divine life, was seen by him—through his misunderstandings of Copernicus and Lucretius—as a vast extension of Hermetic gnosis, of the magician’s insight into the divine life of nature.[4]

Just so there is no ambiguity as to Bruno’s loyalties, Yates elaborates, “Giordano Bruno’s Egyptianism was demonic and revolutionary, demanding full restoration of the Egyptian-Hermetic religion.”[5] Popular among the Jesuit order, the hermetic writings combine Greek philosophy with Eastern religion. This is an interesting amalgamation paralleling Bruno’s life work in that he contributed both to modern science and to the development of Renaissance occultism.

On the other hand, Karen Silvia de León-Jones rejects the popular view of Bruno as hermetic magus and depicts him foremost as a Kabbalist. Kabbalah, meaning “tradition,” is the Jewish mysticism that arose in the twelfth century by interpreting the Torah according to secret or hidden knowledge. León-Jones concludes, “Bruno is implementing those ‘angelic superstructures’ through which demons are controlled, and this is precisely demonic magic.”[6] He operated in the transcendent realms, seeking to access the plurality of worlds and alien beings in which Lucretius had only dreamt. He seems knowledgeable of the extraterrestrial channelings in Nicholas of Cusa’s Of Learned Ignorance, because he outlined a method of obtaining god-like wisdom through “Kabbalistic Ignorance” associated with “certain mystic theologians” within his dialogue Cabala of Pegasus.[7] Bruno scholars explain, “To achieve this, individuals must resolve the paradox (by employing a Kabbalistic reading of the Cabala) of arriving at that most vile baseness by which they are made capable of more magnificent exaltation.”[8] This is a strange paradox indeed.

Next week Bruno Part 2

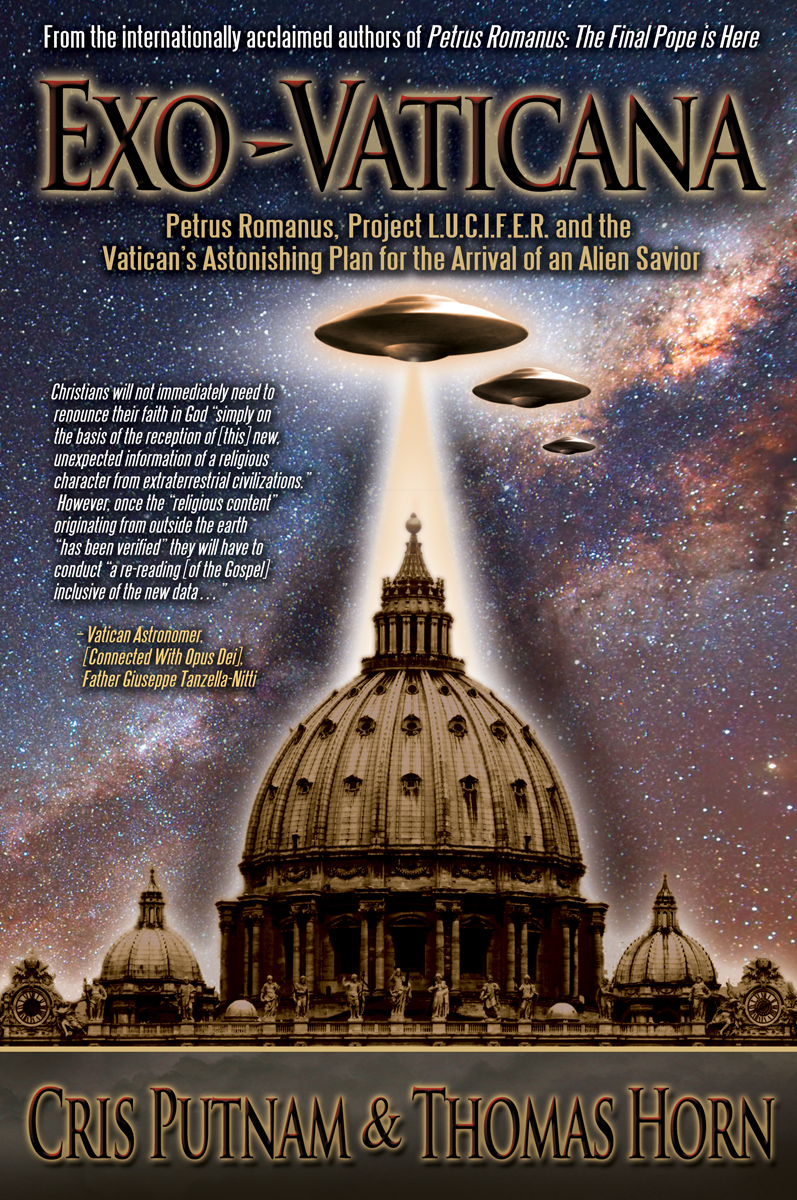

See: http://www.exovaticana.com/

[1] William Turner (1908), “Giordano Bruno,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, (New York, NY: Robert Appleton Company). Viewable here: “Giordano Bruno, New Advent, last accessed January 9, 2013, http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03016a.htm.

[2] Karen Silvia De León-Jones, Giordano Bruno and the Kabbalah: Prophets, Magicians, and Rabbis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 9.

[3] Frances A. Yates, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (New York, NY: Routledge, 1999), 155. See the book here: http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=V5DMa7eWOlkC&lpg.

[4] Frances A. Yates, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, 248. See the book here: http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=V5DMa7eWOlkC&lpg.

[5] Frances A. Yates, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, 422.See the book here: http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=V5DMa7eWOlkC&lpg.

[6] Karen Silvia de León-Jones, Giordano Bruno and the Kabbalah, 21.

[7] Karen Silvia de León-Jones, Giordano Bruno and the Kabbalah, 67.

[8] Giordano Bruno, The Cabala of Pegaus, translated and annotated by Sidney L. Sondergard and Madison U. Sowell (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), xxxii. Viewable here: http://www.yale.edu/yup/pdf/092172_front_1.pdf