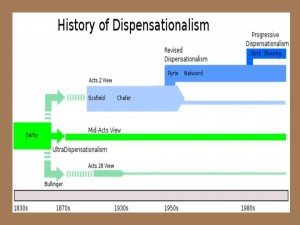

Arguably from the inception of the church (although lost under Romanism), dispensationalism has been and still is the key to biblical prophecy. Since its recovery in the nineteenth century there have been three major versions: classic (Darby, Larkin and Scofield), revised (Walvoord, Pentecost, Chafer, and Towns), and progressive (Bock, Blaising, Feinberg and Saucy) dispensationalism. All divide history based on God’s covenants as successive revelations in the progression of God’s redemptive program and sustain a premillennial futurist interpretation of prophecy. As a founding member of the revised school, Charles Ryrie emphasized three elements: 1) Distinction between church and Israel;[i] 2) Philosophy of History;[ii] 3) Literal interpretation of scripture.[iii] He offers strong and compelling arguments against covenant theology which is the system of theology that centers on two contrived covenants: the covenant of works and the covenant of grace.[iv] It typically dismisses God’s actual covenant promises to Israel and argues that most all of prophecy is fulfilled in Christ. While I’m largely in agreement with Ryrie that covenant theology is an artificial system lacking biblical support, I do think progressive dispensationalists make some good points.

Arguably from the inception of the church (although lost under Romanism), dispensationalism has been and still is the key to biblical prophecy. Since its recovery in the nineteenth century there have been three major versions: classic (Darby, Larkin and Scofield), revised (Walvoord, Pentecost, Chafer, and Towns), and progressive (Bock, Blaising, Feinberg and Saucy) dispensationalism. All divide history based on God’s covenants as successive revelations in the progression of God’s redemptive program and sustain a premillennial futurist interpretation of prophecy. As a founding member of the revised school, Charles Ryrie emphasized three elements: 1) Distinction between church and Israel;[i] 2) Philosophy of History;[ii] 3) Literal interpretation of scripture.[iii] He offers strong and compelling arguments against covenant theology which is the system of theology that centers on two contrived covenants: the covenant of works and the covenant of grace.[iv] It typically dismisses God’s actual covenant promises to Israel and argues that most all of prophecy is fulfilled in Christ. While I’m largely in agreement with Ryrie that covenant theology is an artificial system lacking biblical support, I do think progressive dispensationalists make some good points.

Concerning point one, I strongly disagree with supercessionism (that the church has entirely superseded Israel or replacement theology). I believe God will fulfill His Old Testament promises as they were understood, not in the decontextualized manner applied to the Church found in Roman Catholicism and unfortunately most of evangelical covenant theology. In this sense, the reformers stopped short. God made specific promises to the descendants of Jacob and David concerning their ancestral line, the land and political sovereignty. Only the Mosaic covenant was conditional. The Abrahamic (Gen 12) and Davidic (2 Sam. 7) were unconditional and everlasting. The Davidic is often overlooked:

“And I will appoint a place for my people Israel and will plant them, so that they may dwell in their own place and be disturbed no more. And violent men shall afflict them no more, as formerly, from the time that I appointed judges over my people Israel. And I will give you rest from all your enemies. Moreover, the Lord declares to you that the Lord will make you a house. When your days are fulfilled and you lie down with your fathers, I will raise up your offspring after you, who shall come from your body, and I will establish his kingdom. He shall build a house for my name, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever. I will be to him a father, and he shall be to me a son. When he commits iniquity, I will discipline him with the rod of men, with the stripes of the sons of men, but my steadfast love will not depart from him, as I took it from Saul, whom I put away from before you. And your house and your kingdom shall be made sure forever before me. Your throne shall be established forever.’(2 Sa 7:10–17 cf. 1 Chron. 17)

Like the Abrahamic covenant, the Davidic covenant was irrevocable—“established forever” and despite innumerable acts of unfaithfulness on Israel’s part, God will be absolutely faithful. The Davidic covenant promises to Israel a political, religious, visible earthly kingdom, and God personally guaranteed that it would endure forever and that all nations would be blessed through it, based on His faithfulness.

“I have found David, my servant; with my holy oil I have anointed him, so that my hand shall be established with him; my arm also shall strengthen him. The enemy shall not outwit him; the wicked shall not humble him. I will crush his foes before him and strike down those who hate him. My faithfulness and my steadfast love shall be with him, and in my name shall his horn be exalted. I will set his hand on the sea and his right hand on the rivers. He shall cry to me, ‘You are my Father, my God, and the Rock of my salvation.’ And I will make him the firstborn, the highest of the kings of the earth. My steadfast love I will keep for him forever, and my covenant will stand firm for him. I will establish his offspring forever and his throne as the days of the heavens. If his children forsake my law and do not walk according to my rules, if they violate my statutes and do not keep my commandments, then I will punish their transgression with the rod and their iniquity with stripes, but I will not remove from him my steadfast love or be false to my faithfulness. I will not violate my covenant or alter the word that went forth from my lips. Once for all I have sworn by my holiness; I will not lie to David. His offspring shall endure forever, his throne as long as the sun before me. Like the moon it shall be established forever, a faithful witness in the skies.” Selah( Ps 89:20–37)

God spoke through the original inspired author who certainly did not have an ethereal metaphorical Israel in mind when he composed those words. David understood the promises in a matter of fact manner. I have never read a supercessionist reply to these passages that did not cast God in the role of a prankster who deceived David.

Paul writes in Romans that Gentiles are grafted into Israel. This implies God’s chosen people includes the church as well as a remnant of ethnic Israel, now and especially at the Second Coming (Rom 11:26-27, Zec 12:10). While the distinction applies in this current dispensation due to Israel’s supernatural blinding (Rom 11:25; 2 Cor 3:14; Mat 23:39), I believe we merge into one people at Christ’s return. Thus, I commend the holistic view described by Bock and Blaising, “God will save humankind in its ethnic and national plurality. But, He will bless it with the same salvation given to all without distinction; the same, not only in justification and regeneration, but also in sanctification by the indwelling Holy Spirit.”[v] It seems unlikely that ethnicity will much matter upon Christ’s return to rule from Jerusalem.

Next week part two picks up with the dispensational philosophy of history.

[i] Charles Caldwell Ryrie, Dispensationalism, (Chicago: Moody Publishers, 1995), 148.

[ii] Ryrie, Dispensationalism, 20.

[iii] Ryrie, Dispensationalism, 102.

[iv] Stanley Grenz, David Guretzki and Cherith Fee Nordling, Pocket Dictionary of Theological Terms (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1999), 32.